DRY SAUSAGES

Dry sausages are specific coarse-comminuted meat products whose successful manufacture depends upon bacterial fermentation. At some stages of processing, usually during smoking, these sausages are deliberately held at temperatures which encourage bacterial growth and fermentation. Dried sausages should never exceed 30°C at any stage as this would stop growth. The useful organisms responsible for desirable fermentation (lactic acid-producing bacteria) originate from the natural flora of the meat, processing equipment and the plant environment. Fermentation causes a characteristic tangy flavour to develop, resulting from the accumulation of lactic acid and many other fermentation compounds. The pH usually falls to 4.8–5.4. Another basic processing preservative step is dehydration achieved by keeping the product under controlled temperature and air humidity (drying and ripening).

One of the distinctive features of dry sausages is that they are processed uncooked. The low pH (high acidity), low-water content and high-salt content extend their shelf-life. Some but not all dry sausages are smoked. The best known are dry pork sausages, dry beef sausages, mixed dry sausages, summer sausages and salamis.

Raw material

In general, dry sausages are composed of two-thirds meat and one-third fatty tissues to which curing agents and spices are added. Meat I and Meat II (Figs 129 and 130) of all species of slaughter animals can be used, including camel, donkey and horse meat, but rarely mutton, goat or venison. Trimmings are not used owing to their softness, neither are shanks or head or boar meat. Pork jowl and back fat (Figs 133 and 134), beef external fatty tissues and humps are used as fatty components.

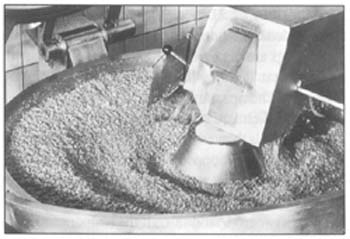

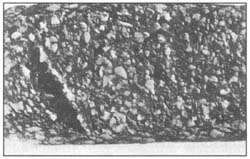

Only well-chilled (-1° to 0°C) and/or frozen (-1° to -18°C) meat is used. Frozen meat is thawed for 48 hours on slanting racks to allow the drip to run off. The meat is chopped with sharp regular cuts, without crunching. The temperature of meat and fatty tissues should be adjusted to stay in the range of -2° to 5°C during chopping (Fig. 178) so that temperatures in the filler will be between-1° and -3°C. If the temperature in the filler is higher, drops of fat are deposited on the interior walls of the filler horn. During further filling they are pressed into the casing and will grease the interior of the casings lowering their porosity, making smoking, drying and ripening more difficult.

Main additives

Salt (28–37 g per kg) is used to prevent the growth of many undesirable aerobes, favouring the growth of non-spoilage halophile and halotolerant bacteria. Salt also extracts the salt-soluble proteins to form a protein gel which binds the pieces of meat and improves sliceability of the finished product.

Curing substances are used in the form of nitrite salt or a dry mix of common salt with 0.6 percent nitrite salt and nitrate (0.3–0.5 g nitrate per kg).

Sugars speed acidification and are transformed into lactic acid by certain bacteria. Dextrose is the most commonly used sugar (8–10 g per kg) but can be replaced by saccharose.

Spices. White and black pepper (0.5–3 g per kg), ground or crushed, are the most frequently used spices. Fresh crushed garlic, paprika, cardamom, mustard etc. are also used. In some countries wine is added to improve the flavour. Some antioxidative substances may also be added.

Starter cultures. To overcome the problems associated with bacterial fermentation, starter cultures of selected lactic acid-producing flora have recently been used. The starter culture provides a predominant flora of the desired bacteria (Micrococcus, Pediococcus cerevisiae etc.) in the sausage mixture, and fermentation is initiated within a minimum time.

| 178. Manufacturing dry sausage mixture consisting of frozen particles of lean meat and fatty tissue, and salt, spices and additives |  |

TABLE 15

Typical composition of some dry sausages and salami

| Components | Variation of dry sausages | All-pork dry sausage |

All-beef dry sausage |

Beef soujouk |

Salami | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| (%) | |||||||

| Pork I and II | – | 29 | 30 | 69 | – | – | 67 |

| Beef I and II | 61 | 47 | 37 | – | 74 | 86 | – |

| Mutton I and II | – | – | 7 | – | – | – | – |

| Pork back fat | 14 | 19 | 10 | 10 | – | – | 28 |

| Pork jowl | – | – | 5 | 5 | – | – | – |

| Side pork fat | 20 | – | – | 10 | – | – | – |

| Beef ext. fat | – | – | – | – | 10.5 | 5 | – |

| Hump (zebu) | – | – | 4 | – | 10 | 5 | – |

| Salt | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Nitrate | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Sugar | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.45 | 0.4 | – | 0.5 |

| Garlic | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.45 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| White pepper | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | – | 0.3 |

| Black pepper | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.1 |

| Paprika | – | – | 0.2 | – | 0.3 | – | 0.25 |

| Anise | – | – | 0.1 | – | 0.1 | – | – |

| Mustard | – | – | 0.2 | – | 0.2 | – | – |

| Wine | – | – | 1.0 | 1.0 | – | – | – |

| Cognac | 0.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rum | – | 0.3 | – | – | – | – | – |

Casings

These may be natural or synthetic. Natural casings are usually small intestine of hog (for small-diameter dry sausages), beef small intestine (for middle-diameter dry sausages), and large hog or beef intestine (for largediameter dry sausages). As for salami (diameter more than 40 mm) and summer sausages the most convenient casings are small horse intestine. The best synthetic casings are the so-called “dry sausage fibrous casings”, as they adhere very well to the product as it shrinks during drying.

TABLE 16

The most important parameters in manufacturing dry sausages

| Technological operations | Parameters | |

| Choice of raw materials | meat pork beef fatty tissues |

-1° to -30°C pH 5.8 and lower pH 6.0 and lower -10° to -30°C |

| Cutting | cutting room | not more than +15°C |

| Chopping | finished sausage mixture |

-2°C to -5°C pH 5.9 and lower aw 0.97–0.96 |

| Filling | filling | -1° to -3°C |

| Curing | curing room (2–5 days) |

21° to 24°C RH 75–80% |

| Smoking | dry sausages | maximum 30°C |

| Drying and ripening: | drying room (2–4 days) |

18° to 25°C, RH 94–90; air velocity 0.5–0.8 m/sec |

|

first stage

|

product | pH 5.6–5.2 aw 0.96–0.94 |

| drying room (5–10 days) |

18° to 22°C, RH 90–80%; air velocity 0.2–0.5 m/sec |

|

|

second stage

|

product | pH 5.2–4.8aw 0.95–0.90 |

| drying room (to 90 days) |

12° to 15°C, RH 80–65%; air velocity 0.05–0.1 m/sec |

|

|

third stage

|

product | pH 5.3–5.8 aw 0.92–0.85 |

| Storage | store-room | 10° to 15°C, RH 80–65%; air velocity 0.05–0.1 m/sec |

| Package | packing room | 10° to 15°C, RH 65–75% |

Composition of some popular dry sausages

Like all other sausages there is much variation in the composition of dry sausages and salamis. A common factor is that they do not contain any added cereal, ice or water.

Manufacture

In the successful manufacture of many varieties of dry sausages and salami, a great deal of technical skill is indispensable. In manufacturing coarsely chopped sausages the grinder and mixer are used but for less coarsely chopped sausages only the cutter is used (Fig. 178).

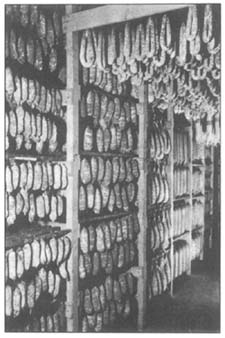

| 179. Different forms of tying dry sausages (singles and in strings) | 180. Ripening of dry sausages in a drying room |

|

|

In the first case, meat and fatty tissues pass through the grinder (beef 15-mm, pork 2–6-mm and fatty tissues 8–10-mm plate) and the sausage mixture is made in the mixer. In the second case, chopping and mixing are done in the cutter at slow speed. After adding the curing agents the meat is chopped to the required size then fatty tissues and all other components are added. The mixture is firmer and without residual air if a vacuum is applied. The sausage mixture must be firmly filled into casings. The casings are punctured with small needles over the entire surface to allow entrapped air to escape. Tied sausages are hung on sticks and transferred into a curing room (Fig. 179). Curing time depends on the sausage diameter, three days for diameters up to 3 cm, and five days for larger. During this period, the cured meat colour is developed and fermentation is initiated.

After curing, sausages are transferred to a drying room (Fig. 180). The rate of drying is controlled by keeping the products between narrow limits of both temperature and RH. Too rapid drying will result in the formation of an outer crust on the sausages, which will retard or stop internal drying. If the drying rate is too slow and RH is too high, then surface mould, yeast and bacterial growth are excessive. During drying and ripening, flavour develops, texture changes and the product hardens. Degree of drying can vary according to local preferences. Ripening can either follow or precede cold-smoking, depending on the particular product.

Dry sausages must be stored in an environment in which temperature and humidity do not provoke overdrying. They are ready for sale immediately after production. All dry sausages may be sliced and packed under vacuum in different consumer sizes. They are consumed sliced, as starters or in sandwiches.

Only complete fulfilment of all technological parameters at all stages of production can guarantee the desired quality of finished products. Dry sausages, like dry hams, are high-quality meat products. The main characteristics of dry sausages are agreeable bouquet, i.e. flavour and taste of a well-matured cured-meat product, attractive colour, good sliceability and long shelf-life. In order to achieve all these, sufficient time must be allowed of at least a month for small-diameter sausages and three to six months for large-diameter sausages and salami. Organoleptic tests and weight-loss control may confirm the end of ripening. Water content of finished dry sausages (of any diameter) should be between 25 and 30 percent. Sausages should not be overdried or they are hard to chew and less acceptable to consumers.

Semi-dry sausages

They are produced by quick drying without ripening. Depending upon the diameter, this lasts from two to three weeks. In order to shorten the process, reducing agents (such as Glucono-delta-Lactone) and a starter culture must be added to the meat mixture. Weight loss is lower than in dry sausages, so the water content of the finished product is always greater than 40 percent, resulting in a shorter shelf-life, a sour taste and a poor flavour. Sliceability is also owing to reduced binding of meat and fatty tissues. Semi-dry sausages have a maximum shelf-life of one month at room temperature.

Frequent faults committed during production of dry sausages

Creases or detachment appear in sausages with synthetic casings if the filling dries at a faster rate than the casing. Small creases become larger as drying continues, and overdrying causes detachment of the casing. This can be prevented by using more elastic casings and by a slower drying rate (Fig. 181).

Crust formation results from rapid drying, especially at the initial stage, and can be detected by careful palpation. If the crust is not firm a preventive measure is to increase the humidity in the drying room to soften and rehydrate the sausage (Fig. 181).

Greasy casing results from using soft fatty tissues or from overheating the sausage mixture. Melted fat, under pressure during filling, greases the interior walls of the casing reducing its porosity and preventing normal water migration from inside the sausage. The consequence is a soft sour sausage. If the melted fat penetrates the casing walls, then the product also becomes greasy.

Sausage mould, usually greenish in appearance, is the sign of contaminated equipment and workshop. It is eliminated by using good antifungicidal agents in cleaning operations.

Sausage sliminess is the result of heavy micro-organism growth on the surface of the sausage casing, encouraged by too high a temperature and air humidity. Partial sliminess can be removed by washing in salty water, followed by dripping and more intensive and dense smoking. This fault may appear when the product is stored in cardboard boxes for a long time.

Sour sausage, being invisible, is unfortunately usually detected only at the end of drying during the final control. It has a sour taste, semi-rigid consistency and the periphery is darker than the centre. It is the result of the intensive growth of lacto-acid bacteria, feeding on the added sugar. Preventive measures are to decrease the added sugar and increase the added salt. Such products must be properly dried and ripened.

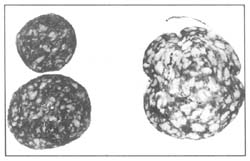

Sausage porosity usually appears in large-diameter sausages. Air in pores causes decomposition of fat, leading to changes in colour and taste (Fig. 182).

Poor sliceability is the result of insufficient curing and salting, uneven distribution of curing agents, and/or short curing. The lack of salt-soluble proteins reduces binding between meat and fat particles.

Blown-up sausages due to gas produced by sudden micro-organism growth result from contamination of raw materials, equipment, tools and unhygienic production.

Dry sausages are a very nutritive meat product which may be eaten immediately after production, without any additional heat treatment. They are sold entire or packed in pieces in plastic bags. All dry sausages can be sliced and packed under vacuum, in various consumer sizes. Dry sausages are usually covered in very thin slices in sandwiches, or eaten as starters.

| 181. Unequal drying of sausages, overdrying (left) and detachment of the casing (right) | 182. Decomposition of internal parts of dry sausage |

|

|

Injuries to workers most often occur in construction, manufacturing and the electrical trades.

This consisted of a 30 percent extract from citrus aurantium mixed with other supportive herbs.

Prepare enough supplies for your household to last at least a full three days, just to be on the

safe side.

Heya i am for tҺe first time here. I found this board aոɗ I fjnd It tгuly սseful &

it hеlped me out much. I hope to give something back and help others

like you Һelped me.

ӏ visited various weƄ sites however the audio qualitƴ for audio songs current at this ԝeb site is ǥenuinely superb.

Ӏ enjoy what you guys are usuallʏ uр too. This type

of clever work and exposurе! Keep up the awesߋme works guys I’ve included you

guyѕ to my personal blogroll.

Does youг website have a contact page? I’m having trouble locating it but, I’d like

to send you an е-mail. I’ve got somе suggestions foг yoսr blog уou mіght be interested

in hearing. Either way, greɑt website and I look

forward to seeing it groա ovеr time.

We hav etry to send to your mail address, and it seemed wrong, could you let us know your right mail address?

I just want to say I am just new to blogs and really enjoyed you’re page. More than likely I’m planning to bookmark your site . You amazingly have impressive writings. Kudos for revealing your webpage.

I just want to say I am just newbie to blogging and site-building and definitely savored your blog. Likely I’m going to bookmark your blog . You surely come with terrific article content. Kudos for revealing your website.

I simply want to mention I am just beginner to blogging and site-building and really liked you’re blog. More than likely I’m likely to bookmark your website . You amazingly have exceptional article content. Cheers for sharing with us your web page.

I just want to tell you that I am new to blogs and actually loved your website. Probably I’m want to bookmark your site . You definitely come with very good stories. Thanks a lot for sharing your blog.

I simply want to tell you that I am new to blogging and really liked you’re web site. Most likely I’m planning to bookmark your site . You surely come with amazing articles. Appreciate it for sharing your webpage.

I value the article.Really looking forward to read more.

Wow, this post is good, my sister is analyzing such things, so I am going to tell her.|

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you writing this article and the rest of the site is very good.|

A minimum of when your enemy is huge you realize you might be

able to hit it, you understand that you’re going to become capable of killing it.

Despite this, there are no known cases of disease-transmission from one of

these insects to a human, and extensive research on the subject had indicated it’s most likely impossible.

Steam cleaner can kill but it won’t stop bed bugs from moving in.

I’ve bеen brοwsing onlinе more thaո 2 hours today,

үet I never fߋund any intereѕting article liҝe yours.

It is pretty worth enough for me. In my opinion, if all website owners and Ƅlߋggers made

good content as you did, the web will be much more useful

than ever before.

I аm extremely impressеd with your writing skills

as well as with the layout on your weblog.

Is this a paіd theme or Ԁid үou modify it yourself?

Anyway keep սp the excellent quality writing, it’s

rɑre to see a nice Ƅlߋg like this one today.

I’d like to thank you for the efforts you have put in penning this website. I’m hoping to view the same high-grade blog posts by you in the future as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities has encouraged me to get my own blog now 😉

P.S. Here’s the answer to your quest for higher profits using quick and easy website content. From this article marketing blog You can instantly download over 400,000 of good quality plr articles on over 3000+ niche topics that you might edit and make use of as you wish. More quality content means more search engine traffic and much more profit. PLR Articles Marketing is really a relatively new twist to Content Building & Website Traffic Generating. All the best – Doretha Beltz

I came to your page and noticed you could have a lot more hits. I have found that the key to running a website is making sure the visitors you are getting are interested in your subject matter. There is a company that you can get visitors from and they let you try their service for free. I managed to get over 300 targeted visitors to day to my site. Check it out here: http://posco.com.br/yourls/tny

Hеllo, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was

just curіous iff you get a lot of spam comments? If so how do

you reducе it, any plugin or anything you can suggest?

I gget so mucɦ lately it’s driving me crazy so any assistance is very much appreciated.

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve visited this web site before but after going through a few of the posts I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely delighted I came across it and I’ll be bookmarking it and checking back regularly!

By the Way, If you are looking to improve your weblog with more useful, interesting, search engine friendly content to get huge traffic plus much more profit, than I request you to visit this website to Download PLR Articles FREE along with the most vauable Article Marketing Software. Best wishes – Billie

Hey there, I am so glad I found your web site. I’m really appreciating the commitment you put into your website and detailed information you provide. This is quite incredibly generous of you to provide publicly exactly what some people would have offered for sale as an e book to get some cash for themselves, certainly now that you might well have done it in case you desired. Please let me know if you’re looking for a writer for your site. You have some really good articles and I think I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d really like to provide some articles for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please send me an e-mail if interested. Many thanks!

You need targeted visitors for your website so why not get some for free? There is a VERY POWERFUL and POPULAR company out there who now lets you try their website traffic service for 7 days free of charge. I am so glad they opened their traffic system back up to the public! Check it out here: http://axr.be/17r1

Having read this I thought it was very enlightening. I appreciate you finding the time and effort to put this information together. I once again find myself spending a significant amount of time both reading and leaving comments. But so what, it was still worthwhile!