3. Results and Discussion

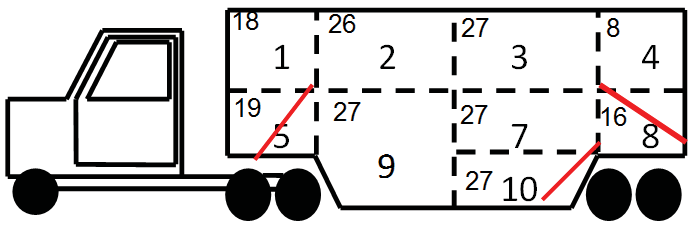

No significant effect of the trailer compartment as a single factor or in interaction with the season was found on any physiological or meat quality variable (data not shown). Hence, data were pooled across compartments in order to study the effects of the deck (upper deck or UD = compartments 1+2+3+4; middle deck or MD = compartments 7+8; bottom deck or BD = compartments 9+10) or trailer section (bottom-nose or BN = compartment 5) on these variables.

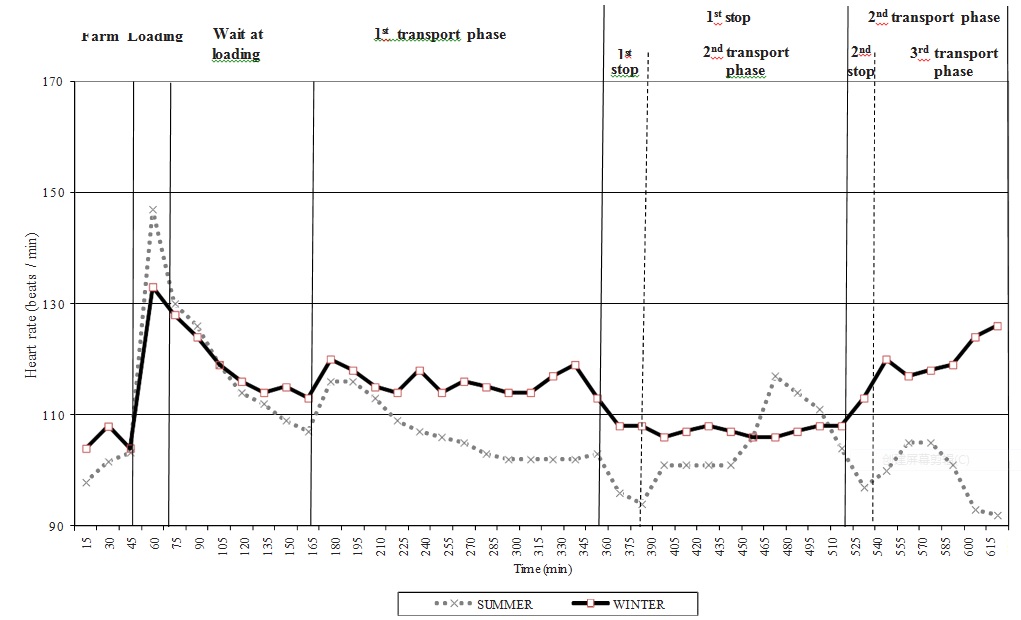

Figure 2. Heart rate from loading at the farm to 8 h transit time of pigs transported in a pot belly trailer in summer (six journeys) and winter (five journeys).

3.1. Physiological Response to Transport

As shown in Figure 2, heart rate was higher (P < 0.001) at loading in the summer, which may be explained by the increased frequency of slips, balks and vocalizations on the loading chute and truck ramp observed in this season compared to winter in a companion study. A higher (P < 0.001) heart rate was also recorded during the first transport phase in winter. The increased heart rate in the initial transport phase during winter transports may be explained by the animal’s need to maintain the body temperature and to maintain balance while the truck was in motion as in a companion study pigs stood more at the beginning of the journey in winter than in summer transports. More recently, Goumon et al. It reported higher heart rates and more pigs standing during the initial phase of transport using a similar PB trailer in winter. It is usually reported that pigs mostly stand in the initial phase of transport as they usually need time to acclimate in the truck after the departure from the farm.

An interaction was found between animal location in the PB trailer and season on pigs’ heart rate, with pigs in the UD and MD showing a greater heart rate during the wait after loading in summer (P = 0.01; Table 1). The higher heart rate recorded in pigs loaded on the UD may result from their physical effort to negotiate the steep ramp to have access to this location. Whereas, the loading order may explain the higher heart rates in pigs located in the MD as this was the last deck to be loaded and pigs were still under the effects of loading stress at the time of departure from the farm.

Table 1. Effects of animal location during transport on the pot-belly (PB) trailer on heart rate 1; average values in summer (Truck location 2).

| Transport phase | Total time (min) | UD | BN | MD | BD | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 78 | 18 | 36 | 48 | |||

| Farm | 120 | 95 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 2.19 | 0.74 |

| Loading | 5 | 152 | 154 | 147 | 146 | 5.23 | 0.54 |

| Waiting at loading | 120 | 124a | 115b | 129a | 126a | 2.61 | 0.01 |

| First transport phase | 190 | 109 | 106 | 109 | 104 | 2.32 | 0.29 |

| First stop | 30 | 95 | 97 | 94 | 95 | 2.09 | 0.88 |

| Second transport phase | 140 | 108 | 105 | 107 | 103 | 2.01 | 0.22 |

| Second stop | 15 | 97 | 94 | 97 | 96 | 2.57 | 0.93 |

| Third transport phase | 45 | 104 | 106 | 107 | 101 | 3.20 | 0.51 |

2 UD: upper deck (compartments 1,2, 3,4);

BN (compartment 5);

MD (compartments 7,8);

BD (compartments 9,10);

a,b Within a row, least squares means lacking a common superscript differ at P < 0.05.

Table 1. Effects of animal location during transport on the pot-belly (PB) trailer on heart rate 1; average values in winter(Truck location 2).

| Transport phase | Total time (min) | UD | BN | MD | BD | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 65 | 15 | 30 | 40 | |||

| Farm | 120 | 107 | 102 | 103 | 105 | 2.06 | 0.27 |

| Loading | 5 | 135 | 139 | 128 | 133 | 2.96 | 0.15 |

| Waiting at loading | 120 | 120 | 126 | 125 | 122 | 2.86 | 0.25 |

| First transport phase | 190 | 118 | 118 | 112 | 116 | 2.20 | 0.15 |

| First stop | 180 | 108b | 112a | 102c | 110ab | 2.11 | 0.02 |

| Second transport phase | 90 | 122a | 125a | 114b | 123a | 2.84 | 0.06 |

2 UD: upper deck (compartments 1,2, 3,4);

BN (compartment 5);

MD (compartments 7,8);

BD (compartments 9,10);

a,b,c Within a row, least squares means lacking a common superscript differ at P < 0.05.

Although a couple of companion papers reported a greater behavioral response (more slips and vocalizations) to loading on the UD and colder temperatures in this deck during winter transports , heart rates of pigs did not differ between truck locations at any time in this season in this study (Table 2).

As no interaction was found for blood variables between season and animal location in the trailer, data were pooled and presented for each variable separately. Consistent with heart rates, both blood lactate and CK concentrations were higher (P < 0.001) in winter than in summer (Table 3). Higher lactate and CK concentrations are usually observed in blood of pigs subjected to rigorous physical exertion as a result of muscle tissue damage. As such, both blood parameters are indicators of muscle fatigue, but in response to different types of stressors. Based on the relatively rapid rate of plasma lactate concentration increase (4 min) and return to basal levels (2 h) after physical exercise, the greater blood lactate concentrations at slaughter in winter than in summer may reflect the greater activity (longer latency to rest) in the lairage pen observed in a companion study in this season. In this season pigs were thus more fatigued at slaughter as they stood more than lying in lairage and could not recover from transport and handling stress. Áveros et al. and Seddon et al. also found elevated exsanguination blood lactate concentrations in winter compared to summer.

Table 3. Lactate and creatine kinase (CK) concentrations in exsanguination blood of pigs (n = 329) transported on the PB trailer according to the season and the truck location.

| Season | Truck location 1 | P –value |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | Winter | SE | UD | BN | MD | BD | SE | Season | Location | |

| CK (UI/L) 2 | 4,605.8 | 6,865.8 | 5,695 | 5,892 | 4,760 | 6,327 | <0.001 | 0.20 | ||

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 10.4 | 13.3 | 0.5 | 12.2b | 14.2a | 10.1c | 11.9b | 0.7 | <0.001 | 0.10 |

BN (compartment 5);

MD (compartments 7,8);

BD (compartments 9,10);

2 CK: Creatine kinase (SE is not presented because CK data have been calculated with inverse transformation);

a,b,c Within a row, least squares means lacking a common superscript differ at P < 0.05.

Higher (P = 0.01) blood lactate concentrations were also observed in pigs transported in the BN compartment. This increase may be associated to the response to peri-mortem handling in pigs having experienced a previous physical stress while negotiating the two ramps, of which one was very steep (32°), to access to this truck location.

Similar to blood lactate concentrations, blood CK levels were greater (P < 0.001) in winter than in summer. Correa et al. also reported higher blood CK levels in winter than in summer. Differently from blood lactate, CK concentration in blood is strongly correlated with long-term physical stress as it reaches a maximum concentration peak 6 h after the physical effort and does not return to basal levels until 48 h afterward. Based on its dissipation pattern in blood after stress, the higher blood CK concentrations in winter in this study may reflect the greater fatigue of pigs at slaughter in this season. In this study, fatigue may be associated to the higher incidence of slips and falls at loading recorded in winter. All these events may have resulted in muscle tissue damage and increased CK release into the blood flow. Similar to Correa et al., animal location within a PB trailer had no effect on blood CK concentrations at slaughter.

3.2. Carcass Quality Traits

On average, HCW of the population under study was 95.7 kg (ranging from 65.5 to 129.8 kg) and the carcass lean percentage was 61.2% (ranging from 55.1 to 66.6%).

Overall, skin damage score and the proportion of carcasses showing fighting-type bruises were higher (P = 0.02 and P < 0.001, respectively) in the summer transports compared to the winter ones (Table 4). The higher skin damage score in summer may be associated with the increased frequency of slips on the loading chute and truck ramp and slips, falls and overlaps observed at unloading in a companion study. The reduced proportion of bruises in winter in this study contradicts the results from previous studies which either reported a higher incidence of bruised carcasses in this season due to increased fighting or mounting behavior in pigs huddling to maintain their body temperature or which failed to find a seasonal variation in skin bruise scores.

Table 4. Skin damage score and percentage of bruised carcasses of pigs transported on the PB trailer according to the season and the truck location.

| Season | Truck location 1 | P –value |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | Winter | SE | UD | BN | MD | BD | SE | Season | Location | |

| N | 257 | 215 | 185 | 55 | 104 | 129 | ||||

| Skin damagea | 2.3 | 2.1 | 0.046 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.42 |

| Fighting type bruiseb % | 46.5 | 24.7 | 36.8 | 38.2 | 35.6 | 35.7 | <0.001 | 0.80 | ||

| Mounting type bruisec % | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.99 | 0.68 | ||

| Other type of bruisesd % | 21.3 | 21.9 | 23.2 | 21.8 | 17.3 | 23.3 | 0.96 | 0.75 | ||

BN (compartment 5);

MD (compartments 7,8);

BD (compartments 9,10);

a Based on the MLC scale from 1 (none) to 5 (severe);

b Percentage of carcasses with more than

10 fighting-type bruises according to the ITP scale;

c Percentage of carcasses with more than 5 mounting-type bruises according to the ITP scale;

dPercentage of carcasses presenting bruises of different origin (lacerations, scratches, etc.)

The greater proportion of fighting-type bruises recorded in the summer compared to winter is hard to explain considering that pigs laid more during transport and took shorter time to rest in the lairage pen after transport in summer compared to winter.

Despite the variation in pig postures observed between truck compartments at unloading, with pigs from the top compartments being slower to move out and those from the bottom compartments overlapping more, bruise score did not vary between truck locations in this study. This discrepancy between pigs’ posture observation in the truck and bruise scores has been also reported by Scheeren et al. it using a similar PB trailer model.

3.3. Meat Quality

It is known that cold and heat stress have an impact on ante- and post-mortem muscle glycogen stores leading to higher incidence of DFD and PSE pork, respectively [8,9]. As expected, pH24 values were greater (P < 0.001) in the LT, and SM and AD muscles in winter than in summer (Table 5). Consistently, in winter the LT muscle had lower (P = 0.001) drip loss and higher (P = 0.02) subjective color score (darker color). However, in the SM muscle pH6 value was lower (P < 0.001) and drip loss value was higher (P = 0.03) in winter than in summer. Both meat quality traits are indicative of increased muscle acidification which may result in PSE pork. O’Neill et al. sombody also reported a higher prevalence of PSE meat in winter compared to summer and hypothesized that it was related to faster slaughter rates in winter. To maintain fast slaughter speeds, handlers push pigs to walk at a faster pace resulting in acute physical stress immediately before slaughter. It is not surprising that this effect is more pronounced in a locomotory muscle, such as the SM, as this muscle is more susceptible to physical exercise.

Table 5. Meat quality variation as measured in the Longissimus thoracis (LT), Semimembranosus (SM) and Adductor (AD) muscles of pigs transported on a PB trailer according to the season and the truck location.

| Season | Truck location 1 | P –value |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | Winter | SE | UD | BN | MD | BD | SE | Season | Location | |

| N | 270 | 225 | 198 | 55 | 110 | 132 | ||||

| LT muscle pH 24h | 5.64 | 5.73 | 0.01 | 5.69a | 5.70a | 5.66b | 5.66b | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| LT muscle L* | 49.19 | 49.04 | 0.26 | 49.32 | 48.29 | 49.09 | 49.12 | 0.36 | 0.67 | 0.34 |

| LT muscle a* | 8.43 | 8.16 | 0.09 | 8.34 | 8.16 | 8.30 | 8.25 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.81 |

| LT muscle b* | 4.91 | 4.90 | 0.08 | 4.96 | 4.62 | 4.95 | 4.92 | 0.12 | 0.94 | 0.29 |

| LT muscle JCS2 | 2.94 | 3.11 | 0.06 | 3.02 | 3.18 | 3.00 | 2.98 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.42 |

| LT muscle EC3 | 6.99 | 7.49 | 0.17 | 7.57a | 7.21a | 7.20a | 6.87b | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| LT muscle Dop Loss % | 4.05 | 3.39 | 0.14 | 3.70 | 3.21 | 3.89 | 3.83 | 0.20 | 0.001 | 0.19 |

| SM muscle pH 6 h | 6.32 | 6.07 | 0.02 | 6.18 | 6.21 | 6.19 | 6.21 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.86 |

| SM muscle pH 24h | 5.63 | 5.71 | 0.01 | 5.66 | 5.76 | 5.65 | 5.69 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| SM muscle L* | 46.84 | 46.19 | 0.21 | 46.86a | 46.24ab | 46.69a | 45.97b | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| SM muscle a* | 7.90 | 8.64 | 0.10 | 8.28 | 7.85 | 8.47 | 8.27 | 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.08 |

| SM muscle b* | 3.69 | 4.08 | 0.07 | 3.96a | 3.68b | 4.01a | 3.79a | 0.09 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| SM muscle EC3 | 6.88 | 6.98 | 0.18 | 7.17 | 6.62 | 6.86 | 6.67 | 0.26 | 0.68 | 0.30 |

| SM muscle Dop Loss % | 3.77 | 4.15 | 0.13 | 4.17a | 3.76b | 3.98ab | 3.96ab | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.002 |

| AD muscle pH 24h | 5.81 | 6.01 | 0.02 | 5.91a | 5.97a | 5.84b | 5.92a | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

BN (compartment 5);

MD (compartments 7,8);

BD (compartments 9,10);

2 According to Japanese Color Scales (from 1 = pale to 6 = dark);

3 Electrical conductivity measured by the PQM (Pork Quality Meter, Aichach, Germany);

a,b,c Within a row, least squares means lacking a common superscript differ at P < 0.05.

Meat quality was also affected by animal location during transport, with pigs located in the BN and UD having higher (P = 0.02) pH24 values (Table 5). Similar to the effects of the season, the effects of transporting pigs in the BN were more pronounced in locomotor muscles, with SM and AD muscles of these pigs showing higher (P < 0.001 and P = 0.002, respectively) pH24 values. Lower L* values and drip loss percentages (P = 0.03 and P = 0.002, respectively) were also reported in the SM muscle of pigs transported in the BN. These meat characteristics indicate that pigs loaded in the BN area may become fatigued and be prone to produce DFD pork.

4. Conclusions

This study shows that some pot-belly trailer locations, such as the upper deck and bottom- nose, impose a certain level of stress on pigs during transport resulting from the use of internal ramps at loading and unloading. Additional studies are needed to determine means of reducing the stress of moving pigs into and out of such trailer locations. Although in this study the effect of the season may have been confounded by the different transport schedule between seasons, which reflects the commercial practice in the Canadian Prairies, the greater physical exhaustion (higher blood lactate and CK levels, and pH24 values) of pigs transported long distance in winter which is due to the additive effect of cold stress confirms results that have been previously reported in the literature.

Acknowledgments

This research project was funded by NSERC, Alberta Pork, SaskPork, Manitoba Pork, Ontario Pork and Maple Leaf Foods. We appreciate the technical assistance of Sophie Horth, Frederic Morel, Thusith Samarakone, Stephanie Hayne, Crystal Kappel, Megan Bouvier, Brenda Sawatzky, José Rodolfo Ciocca, Angela Vanelli Weschenfelder and Andreanne Bornais for the data collection at the slaughter plant, blood sampling, meat quality measurements and laboratory analysis, and Steve Méthot for the statistical analysis. The authors are grateful to Steve’s Livestock for providing the transport and Maple Leaf Foods for providing manpower and facilities. J. A. Correa thanks Fulgence Ménard Inc. for allowing him pursue his Ph.D. studies during the working hours.

I just want to tell you that I am just very new to weblog and certainly savored your web blog. Most likely I’m want to bookmark your blog post . You really come with great writings. Regards for sharing with us your web page.

I just want to say I am beginner to weblog and certainly loved you’re blog. Almost certainly I’m going to bookmark your website . You surely have tremendous articles and reviews. With thanks for sharing your web page.

Hey there, I am so happy I found your web site. I’m really appreciating the commitment you put into your website and detailed information you present. It has been so particularly generous of you in giving easily exactly what a number of us would’ve distributed for an electronic book to generate some cash on their own, notably considering that you could have done it if you wanted. Please let me know if you’re looking for a article author for your weblog. You have some really good posts and I think, if you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d absolutely love to provide some articles for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please blast me an email if interested. Kudos! P.S. Go Get Free Content For Your Blog & Free Article Marketing Software <<< Here

Fantastic website. Plenty of helpful info here.

I am sending it to a feww pals ans additionally sharing in delicious.

And naturally, thank you to youir effort!

I simply want to mention I’m newbie to weblog and actually liked this website. Likely I’m going to bookmark your site . You amazingly come with excellent articles and reviews. Cheers for sharing with us your web page.

I just want to tell you that I am beginner to weblog and seriously loved your web-site. Probably I’m planning to bookmark your website . You amazingly have exceptional articles and reviews. Kudos for revealing your website page.

hi!,I like your writing very a lot! share we be in contact extra approximately your post on AOL? I need an expert on this space to solve my problem. Maybe that’s you! Taking a look ahead to peer you.

Hello there! I know this is kinda off topic but I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My website covers a lot of the same topics as yours and I think we could greatly benefit from each other. If you’re interested feel free to shoot me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Terrific blog by the way!

With havin so much content do you ever run into any problems of plagorism or copyright infringement? My site has a lot of unique content I’ve either authored myself or outsourced but it seems a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my agreement. Do you know any ways to help protect against content from being ripped off? I’d really appreciate it.